“The two ministerials show how important it is to work together to close the gaps in energy access, promote economic growth, and make sure that the energy transitions in developing countries are in line with the Paris Agreement’s global climate goals.” We need to turn our promises into actions that will make a difference around the world.

— Damilola Ogunbiyi, CEO of Sustainable Energy for All (SEforALL), speaking at the Global Ministerial for Energy Access in March 2025

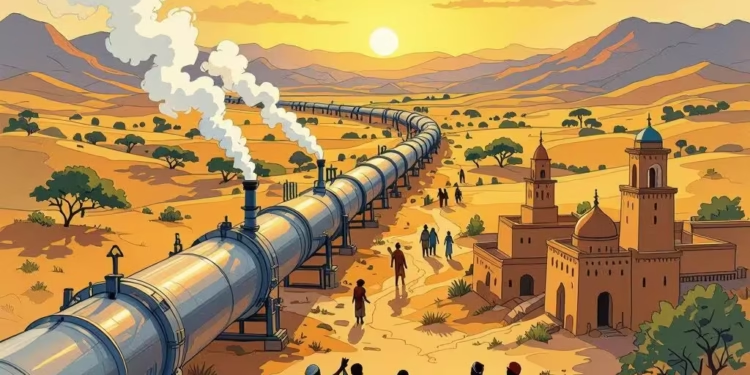

The statement above sums up the diplomatic spirit behind Africa’s most ambitious cross-border infrastructure project, the Morocco-Nigeria Gas Pipeline (NMGP). As a senior diplomat who has worked on many international energy negotiations, I have seen how these kinds of projects go beyond just making money and affect the way regions come together, energy security, and political alliances. This article gives a thorough diplomatic look at the NMGP, using official communications, academic research, and lessons learned from working together on energy issues with other countries.

Introduction: Energy Diplomacy in an Africa That Is Changing

The NMGP is more than just a pipeline; it is a diplomatic tool, a sign of Africa’s power, and a way to see if the continent can build complicated infrastructure in a world that is always changing. The NMGP’s path teaches both international relations professionals and students important lessons in a time of changing energy partnerships, climate concerns, and renewed competition between great powers.

The Strategic Context: What the NMGP Means

Energy Security and Bringing Regions Together

The lack of energy in Africa is still one of the continent’s biggest problems when it comes to development. Almost 600 million people in Sub-Saharan Africa don’t have access to electricity, which slows down economic and social progress. The NMGP is a network of pipelines that runs through 16 countries and covers more than 5,600 kilometers. It is meant to bring up to 30 billion cubic meters of natural gas from Nigeria’s huge reserves to Morocco and then to Europe every year. It is a key part of the Mission 300 initiative, which wants to connect 300 million Africans to electricity by 2030, because of its size and goals.

Mapping stakeholders and diplomatic architecture

The diplomatic structure of the pipeline is very complex. It is based on a number of Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) signed between Nigeria, Morocco, and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). There are also bilateral agreements with transit countries like:

- Benin

- Togo

- Ghana

- Côte d’Ivoire

- Liberia

- Sierra Leone

- Guinea

- Guinea-Bissau

- The Gambia

- Senegal

- Mauritania

The African Union (AU), the World Bank, and the European Investment Bank are also supporting the project, which shows that it fits with both continental and global energy strategies.

The Moroccan Sahara and Geopolitical Competition

The NMGP’s path through the Moroccan Sahara has important geopolitical meaning. The US, France, Spain, Germany, and Gulf countries have all recognized Morocco’s right to rule the area. This gives Rabat more power in diplomacy and gives the Dakhla pipeline terminal a lot of credibility. This recognition not only strengthens Morocco’s position as a leader in the region, but it also acts as a counterweight to Algeria’s competing Trans-Saharan Gas Pipeline (TSGP) project, which makes the strategic competition between North Africa’s two energy giants even stronger.

Historical Development: From Idea to Action

African Energy Diplomacy: Past Examples

The NMGP is based on the West African Gas Pipeline (WAGP), which has linked Nigeria to Ghana, Benin, and Togo since 2010. The West African Gas Pipeline Authority (WAGPA) is in charge of the WAGP’s governance model. This model teaches us a lot about how to make rules that work across borders and how to settle disputes. As a diplomat, I’ve seen how these kinds of frameworks lower the cost of doing business and build trust between different groups.

The Path to the Final Investment Decision

The NMGP’s path has not been straight. The first agreements were signed in 2017, but the Final Investment Decision (FID) has been pushed back several times to take into account technical, environmental, and political factors. By July 2025, feasibility and engineering studies will be done, and a special-purpose company will be set up to oversee implementation. The FID is expected to be done by the end of the year. This step-by-step method shows diplomatic caution by allowing for risk reduction and flexible planning.

Challenges and Opportunities in Diplomacy

Dealing with security risks in the region

The pipeline’s route goes through a number of states that are politically unstable and face security threats, especially in the Sahel. Strong security measures and multilateral monitoring systems are necessary, as shown by past multilateral projects like the Chad-Cameroon oil pipeline. The supporters of the NMGP have called for better security cooperation and planning for emergencies led by ECOWAS to deal with these weaknesses.

Funding and partnerships with many countries

To get the $25 billion investment, you need a mix of public and private money, with help from development banks and investors from Gulf states. The World Bank, the African Development Bank, and the European Investment Bank have all said they will strongly support the project. The United Arab Emirates has also become a major source of funding. Based on my work with Power Africa and other similar projects, I can say that these kinds of different financing structures are very important for making big projects less risky and making sure they last for a long time.

Regulatory Harmonization and Institutional Capacity

The NMGP will only be successful if the laws and rules in all of the countries that are part of it are the same. The African Single Electricity Market (AfSEM) and the Continental Power Systems Masterplan (CMP) are two of the AU Agenda 2063’s most important projects. They both show how to make things work together across the continent. It is hoped that the pipeline’s governance model will use these frameworks to make getting permits, running the pipeline, and settling disputes easier.

The Pipeline as a Tool for Diplomacy

Helping to Bring Together Economies in the Region

The NMGP helps West Africa’s economy come together, build industries, and create jobs. It is expected to give more than 400 million people access to energy, which will boost industrial growth and lower energy poverty. The pipeline also helps develop the regional value chain by connecting gas production in Nigeria to processing and distribution hubs in Morocco and other places down the line.

Improving Energy Relations Between Africa and Europe

The NMGP makes Africa and Europe more dependent on each other by linking African gas supplies to the European market. The project fits with the EU’s REPowerEU strategy, which aims to reduce reliance on Russian gas and encourage partnerships between Africa and renewable energy sources. The Africa-EU Green Energy Initiative (AEGEI) and the Global Gateway Strategy show that Europe is serious about investing in infrastructure that will last on the continent.

Giving Morocco more diplomatic power

Morocco’s role as a transit and terminal country gives it more diplomatic power with both African and European partners. The pipeline strengthens Morocco’s position as a regional energy hub and gives it more power in the AU and ECOWAS. The fact that other countries recognize Morocco’s sovereignty over the Sahara makes Rabat’s negotiating position even stronger. It also protects Morocco from separatist stories and outside interference.

Table of Comparison: Competing Gas Pipeline Projects

| Project Name | Route | Estimated Cost | Capacity (bcm/year) | Status (2025) | Strategic Objective |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morocco-Nigeria Gas Pipeline | Nigeria, Benin, Togo, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Gambia, Senegal, Mauritania, Morocco, and Europe | $25 billion | 30 | FID pending | Regional integration, Africa-Europe supply |

| Trans-Saharan Gas Pipeline | Nigeria–Niger–Algeria–Europe | $13 billion | 30 | Security delays | Algerian leverage on competing export route |

| West African Gas Pipeline | Nigeria, Benin, Togo, and Ghana | $1 billion | 5 | Operational | Regional trade, basis for NMGP |

Diplomatic Narratives: Voices from the Field

I’ve been in negotiation rooms where the future of these kinds of projects is decided throughout my career. The signing ceremony for the NMGP’s MoU in Rabat, which was attended by representatives from ECOWAS, the AU, and several national governments, showed how confident Africa is in its new diplomatic skills. The Nigerian National Petroleum Company’s claim that the project will “help drive the monetization of Nigeria’s gas resources, maintain NNPC Ltd.’s energy leadership in Africa, and promote economic and regional cooperation among African countries” is in line with what most diplomats think about the pipeline’s potential to change things.

Addressing Limitations and Counterarguments

Concerns about the environment and society

Some people say that building a lot of gas infrastructure in Africa could make the continent dependent on fossil fuels and slow down the switch to renewable energy. However, supporters say that natural gas is a transitional fuel that is necessary to fill the continent’s energy gap and help the economy grow. The NMGP can be put into place in stages, which makes it possible to connect it to renewable energy corridors like the Africa Clean Energy Corridor and meet the climate goals set out in the Paris Agreement. To lessen the negative effects, environmental impact assessments and land survey studies are still going on.

Risks to security and political stability

There are big risks involved with the pipeline going through weak states. It’s important to have diplomatic backup plans, like different routes and security protocols for multiple countries. The Maghreb-Europe Gas Pipeline, which was disrupted because of tensions between Algeria and Morocco, shows how important it is to have strong ways to avoid conflict and institutions that can handle problems.

Uncertainties in the Market

By 2030, European gas demand is expected to drop by 7% because of the growth of renewable energy sources and energy-saving measures. This makes the NMGP’s long-term viability more risky from a business point of view. But Africa’s own energy needs are growing, and the pipeline’s design allows for regional supply flexibility, which means it will still be useful even as export markets change.

What we can learn from diplomatic efforts around the world

Power Africa: A Way to Work Together with Many Countries

The U.S.-led Power Africa initiative shows how to use diplomatic power to get investment and technical know-how in the energy sector. Power Africa has doubled access to electricity in a number of countries by using a transactional, demand-driven approach and sending “boots on the ground” experts. The NMGP’s multilateral governance structure is based on the same ideas, with a focus on local ownership, building capacity, and getting the private sector involved.

The Africa-EU Green Energy Initiative: Making Policy and Investment Work Together

The AEGEI, which is part of the EU’s Global Gateway Strategy, shows how aligning policies and providing strategic financing can speed up the delivery of infrastructure. The NMGP’s alignment with AEGEI priorities makes it easier to get European funding and technical help. It also makes sure that African priorities are included in global energy transition frameworks.

The Role of Gulf States in South-South Diplomacy

The UAE and other Gulf countries have become important sources of funding for energy projects in Africa. Their involvement is part of a larger trend of South-South cooperation that works with traditional North-South aid flows. In my experience as a diplomat, these kinds of partnerships make projects more resilient by bringing in money from different sources and encouraging the transfer of technology.

Looking Ahead Situations and Suggestions for Strategy

Scenario Analysis

Best Case: FID achieved by end-2025, construction commences in 2026, and the pipeline delivers gas to both African and European markets by 2030. Regional security stabilizes, and the NMGP becomes a model for continental integration.

Most Likely: Delayed FID (2027-2030), with phased construction and partial capacity utilization. The pipeline primarily serves regional markets, with incremental exports to Europe.

Worst Case: Persistent security and financing challenges lead to project suspension or cancellation, with alternative routes (e.g., Algeria’s TSGP) gaining traction.

Strategic Recommendations for Diplomatic Practitioners

- Strengthen Multilateral Security Cooperation: ECOWAS, AU, and international partners should establish a joint security task force to monitor and protect pipeline infrastructure.

- Prioritize Regulatory Harmonization: Accelerate the adoption of AfSEM and CMP frameworks to streamline cross-border operations.

- Leverage International Recognition: Continue to build diplomatic consensus around Moroccan sovereignty over the Sahara, ensuring the pipeline’s legal and political legitimacy.

- Promote Local Content and Capacity Building: Invest in training and technology transfer to maximize local economic benefits and foster ownership.

- Integrate Climate and Social Safeguards: Ensure robust environmental assessments and community engagement throughout the project lifecycle.

Conclusion: The NMGP as a Diplomatic Legacy

The Morocco-Nigeria Gas Pipeline stands at the intersection of diplomacy, development, and regional transformation. Its realization will depend not only on engineering prowess and financial acumen but on the sustained commitment of African and international diplomats to dialogue, compromise, and shared vision. As we move from commitments to action, the NMGP offers a blueprint for how African agency, strategic partnerships, and diplomatic innovation can reshape the continent’s energy future.

In reflecting on the NMGP’s journey, I am reminded that the true measure of diplomatic success lies not in the signing of agreements, but in the delivery of tangible benefits to the people we serve. The pipeline’s promise—to light up homes, power industries, and knit together a continent—remains a powerful testament to what can be achieved when diplomacy, strategy, and vision converge.